Malaysia’s Big Ambitions

By Abigael Eminza and Claudia Nyon

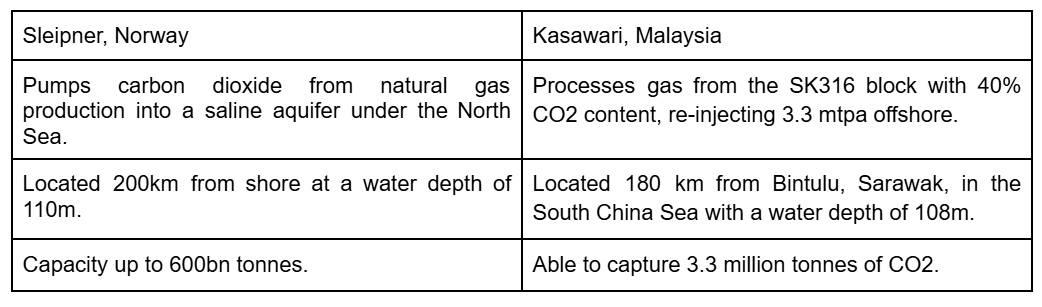

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) has advanced from pioneering offshore projects like Sleipner in Norway to massive new ventures such as Malaysia’s Kasawari development. Sleipner, which began injecting CO2 in 1996, proved that offshore saline aquifer storage was technically feasible, providing decades of operational experience and extensive monitoring data.

Building on this foundation, Malaysia is attempting to commercialize CCS at a scale never before attempted, with Kasawari’s offshore platform designed to process and inject 3.3 million tonnes of CO2 annually from gas with 40% CO2 content. The project is four to five times larger than Sleipner’s, signaling both ambition and unprecedented technical challenges. Together with other announced CCS hubs, Malaysia is positioning itself as a regional leader in carbon storage despite the absence of a dedicated regulatory framework.

The table below shows the differences between the Sleipner project in Norway and the Kasawari project in Malaysia.

IEEFA has compared Sleipner to Malaysia’s CCUS hubs, which are larger by factors of 10 or more. As IEEFA states, “Every proposed project needs to budget and equip itself for contingencies both during and long after operations have ceased” (IEEFA, 2023).

Against this backdrop, Petronas, Malaysia’s national oil and gas company, approved the Kasawari project in November 2022. The project aims to inject 3.3 mtpa of CO₂ underground to monetize a subsea gas deposit with an unusually high CO₂ content of 40% (IEEFA, 2023).

Located in the South China Sea, 180 km north of Bintulu, Sarawak, the Kasawari CCS project draws gas from the SK316 block, which contains an exceptionally high 40% CO2 content. This concentration creates an unprecedented challenge: stripping out, transporting, and storing such a vast volume of CO₂.

To address this, Kasawari’s RM4.5 billion (US$1 billion) CCS component will include the world’s largest offshore CO2 processing platform. With a planned injection capacity of 3.3 mtpa, it will rank among the largest projects globally, second only to Chevron’s underperforming Gorgon project in Australia, at 3.5 to 4 mtpa.

The scale of Kasawari makes system integrity, injection well performance, and storage reliability absolutely critical if long-term CO2 reduction goals are to be achieved. Yet Malaysia has not established CCS regulations, leaving projects of this magnitude to advance without a dedicated regulatory framework.

This lack of precedent is not unique to Malaysia. Globally, governments and industry are proposing CCS storage sites with capacities far beyond those of Sleipner and Snøhvit. The reality is that projects of the scale envisioned for the Houston Ship Channel, the UK CCS clusters, Norway’s Northern Lights, or Malaysia’s Kasawari have never before been attempted.

In this context, Petronas has opted for a Sleipner-like model, performing all gas processing and CO2 recompression offshore on a dedicated platform. However, unlike Sleipner, Kasawari’s platform and equipment will be four to five times larger, making it the world’s biggest dedicated CO2 processing facility.

The unprecedented size and complexity of Kasawari also extend to its contracting strategy. To manage the project’s unique conditions, massive scale, and the risks, both known and unknown, associated with start-up and commissioning, Petronas has adopted an “alliance contracting” risk-sharing structure with Malaysia Marine and Heavy Engineering. While this conservative approach provides a safeguard against unforeseen challenges, it will likely add to the cost of what is already an RM4.5 billion (US$1 billion) component of the overall development.

Malaysia has recently been pivoting itself as being amenable to CCUS facilities being built in the country.

By late 2024, four landmark CCUS projects have been announced:

Petronas Carigali Kasawari-M1: Located offshore Sarawak, the project is scheduled to begin operations in 2026. It is proposed that 60% of the storage capacity will be allocated to Malaysia, for PETRONAS and its partners, with the remaining 40% made available to other users (NS Energy, 2023; Havercroft et al., 2024).

PTTEP’s Lang Lebah-Golok: Located offshore Sarawak, the project is scheduled for operation in 2028. Identified as Malaysia’s second CCS project, the Lang Lebah field holds an estimated 5 trillion cubic feet of gas in place. Development will require the removal of both CO2 and hydrogen sulphide (H2S) (Battersby, 2022).

BIGST Cluster: Estimated to hold around 4 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas. The cluster has remained undeveloped, however, due to its high CO2 content. Given its strategic role in Peninsular Malaysia’s energy security, development will hinge on carbon capture and storage (CCS), positioning it as the first CCS project in the region (Searancke, 2024; Petronas, 2022).

M3 Project: Located offshore Sarawak, East Malaysia. The project is designed to store CO₂ emissions from multiple industries in Japan, including those in the Setouchi region, through injection into offshore Sarawak reservoirs (Battersby, 2024).

According to Malaysia’s National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR), the following CCUS-related targets have been stated.

By 2030:

Develop 3 CCUS hubs (2 in Peninsular Malaysia, 1 in Sarawak) with a total storage capacity up to 15 mTpa (15 million tonnes per annum, mTpa), about 300,000 barrels per day (bpd).

By 2050:

Develop 3 carbon capture hubs with a total storage capacity between 40 to 80 mTpa.

A CCUS bill was planned to be tabled by November 2024, and was pushed forward a few months later. Malaysia’s Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) Bill 2025 has cleared both houses of Parliament and now awaits Royal Assent, with supporting regulations slated to come into force by March 2025 (The Edge Malaysia, 2025; Malaymail, 2025). Championed by Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli, who has positioned himself as the government’s lead architect on industrial decarbonisation, the bill is designed to unlock investment, regulate offshore CO₂ storage, and lay the groundwork for a carbon tax in 2026. Rafizi has argued that Malaysia cannot rely on reforestation alone and must instead leverage its vast depleted reservoirs and offshore capacity to host large-scale CO₂ storage. By providing a legal framework and clear incentives, the bill seeks to position Malaysia as a regional hub for CCUS, attract foreign investment, and generate new revenue streams through state taxes, port fees, and industrial partnerships.

Petronas is pressing ahead with its decarbonisation strategy following the passage of Malaysia’s CCUS Bill 2025, with the flagship Kasawari CCS project now in production and preparing to capture and inject up to 3.3 million tonnes of CO2 annually into the M1 field offshore Sarawak (Lee, 2025). To deliver this, Petronas awarded a RM4.5 billion EPCIC contract to Malaysia Marine and Heavy Engineering (MMHE) in August 2025 for the construction of the world’s largest offshore CO2 processing platform, located about 138 km from shore (The Edge Malaysia, 2022). The platform will be central to Malaysia’s ambition to become a regional CCUS hub, offering storage services beyond domestic demand.

Key findings: Sleipner demonstrated the technical viability of offshore storage but also highlighted the uncertainties of long-term containment, lessons that are highly relevant for Malaysia’s next-generation projects. Kasawari’s scale makes it a global test case for whether CCS can manage very high CO₂ concentrations and sustain multi-million-tonne annual injections. Yet, regulatory gaps, cost escalation risks, and system integrity concerns cast uncertainty over its long-term effectiveness. Malaysia’s broader CCUS roadmap shows strong ambition, but success will hinge on robust oversight and the ability to manage risks at scales far beyond what has been proven to date.

Editor’s Note: After losing the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) deputy presidency to Nurul Izzah Anwar in May 2025, Rafizi submitted his resignation as Economy Minister, effective 17 June 2025. Prior to his departure, he had already completed major tasks like the 13th Malaysia Plan. He is considered to be the key mover of the Bill, making CCUS a high priority.

Worth noting: The debate over CCUS in Malaysia was marked by a division between government-backed initiatives and civil society opposition. The government views CCUS as a key part of its National Energy Transition Roadmap, aiming to position Malaysia as a regional lead in carbon management and kick-starting lots of capital expenditure. State-owned energy company Petronas actively pursues offshore CCS projects, collaborating with international partners like ADNOC and Storegga to enhance CO2 storage capacity (The Edge Malaysia, 2022). But, environmental organizations and opposition lawmakers express significant concerns. Groups such as Greenpeace Malaysia and Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) argue that the CCUS Bill was hastily passed without adequate public consultation, questioning its environmental and social implications (Greenpeace Malaysia, 2025). Furthermore, the Borneo states of Sarawak and Sabah have pushed back on the federal CCUS Bill, seeking more control over CCS projects within their territories.

In this series:

Part 1: Climate Mitigation and the Price of CCUS

Part 2: Case Studies

Part 3: Malaysia’s Big Ambitions

Part 4: Issues for Successful Deployments

Reach us at khorreports[at]gmail.com